There is a common thread that runs through Italy and it bears Dante’s name: if Dante’s journey through the afterlife is also an amazing tour that covers Italian villages, art cities and landscapes, Rome – the city of the two suns “which made the world good” – is certainly one of the stops. Indeed, Rome is the very first city mentioned in the Divine Comedy, when Virgil appears to the poet in Inferno Canto 1.

The Monte Mario Hill, which offered travelers coming from the north the first glimpse of the city, or the Bridge of Castel Sant’Angelo are just two of 18 references to Roman places, monuments and symbols scattered in the Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso. But Dante’s presence and the mark left by his fame can also be seen in the art and culture of the following centuries, through a number of dutiful tributes that the city paid to the poet. Follow us to discover seven “Dante’s places” to celebrate the memory and legacy of the father of the Italian language.

#1 Sant’Angelo Bridge

The statues of the angels that today are its symbol were designed by Bernini and sculpted by his coworkers in the second half of the 17th century but the history of the bridge had begun roughly 1,500 years earlier, during the reign of Emperor Hadrian who had it built to connect his Mausoleum to the other side of the Tiber. Being the only access from the city to St. Peter’s tomb and basilica, the major Christian pilgrimage sites, it was the Roman bridge par excellence for most of the Middle Ages, and also for Dante. In Inferno Canto 18, two groups of sinners moving in opposite direction from each other are thus compared to the many pilgrims passing across the bridge during the Jubilee of 1300 – the first in history – to one side heading towards St. Peter’s, to the other, on their way back, towards Monte Giordano, an artificial hill where Palazzo Orsini Taverna stands today: “as, in the year of Jubilee, the Romans / confronted by great crowds, contrived a plan / that let the people pass across the bridge, / for to one side went all who had their eyes / upon the Castle, heading toward St. Peter’s, / and to the other, those who faced the Mount.” The description is so accurate that many think Dante was one of the approximately two hundred thousand pilgrims who, on average, flocked to the city every day to gain the promised plenary indulgence.

#2 Vatican Museums, Cortile della Pigna

Nimrod is one of the giant Dante meets in Inferno Canto 31. What did he look like…? “His face appeared to me as broad and long / as Rome can claim for its St. Peter’s pine cone; / his other bones shared in that same proportion”: to do the math, the unconventional measurement unit is the colossal bronze pine cone signed by a certain Publius Cincius Salvius, which was almost four meters high and built between the 1st and 2nd centuries AD, in Imperial Rome. The sculpture had been found among the ruins of the Baths of Agrippa, in that part of the city that was already called “Rione Pigna” in 1200, arousing a certain amazement and giving life to the most bizarre legends, for example that it contained the ashes of Emperor Hadrian or that it had been the “plug” of the Pantheon’s oculus. We know that since the 12th century the pine cone was inserted in the fountain for ritual ablutions in the quadrangle of the ancient basilica of St. Peter: it was therefore a sort of landmark for pilgrims visiting Rome, who stopped here to wash themselves and drink. In 1608, with the new basilica under construction, the pine cone was moved to the upper part of the Cortile del Belvedere, to be then be placed a century later where we still admire it today: in the niche of the Cortile della Pigna, on a shelf of the double flight staircase and above a monumental figured capital.

#3 Casa di Dante in Roma

As English traveler Magister Gregorius wrote at the beginning of the 13th century, in Rome “the towers are so numerous that they seem like stalks of grain”. Symbols of power and prestige, bulwarks of defense against opposing families, the towers of medieval Rome were in fact at least 300 and, together with the bell towers of the churches, marked the profile of the city for centuries. We do not know where Dante lived when in September 1301 he was part of the embassy sent from Florence to the Pope, in his only visit to Rome that is certainly attested to, but the Palazzetto degli Anguillara represents a fragment of the city that must have appeared him. Although it mostly dates back to the 15th century and underwent heavy restorations at the end of the 19th century, the fortified complex built by Count Everso II degli Anguillara incorporated an older tower, in a strategic position on the Tiber river opposite the Tiber Island. The building changed hands many times and was also briefly used as an enamel and paint factory, then in 1887 it was expropriated by the Municipality of Rome. With a happy choice, in 1920 it was entrusted to the Casa di Dante, the institution founded in 1914 to promote the study and dissemination of Dante’s work, which has kept its management until today, carrying out research activities, organizing conferences, exhibitions and events. A treasure for fans of the Supreme Poet.

#4 Vatican Museums, Raphael’s Rooms

Not very tall, with a long face shape, a pronounced nose and a melancholy and pensive air: Giovanni Boccaccio, who was a passionate lover of Dante and his work, describes with this words the poet in the mid-14th century. Dante’s fame grew however so rapidly that his portraits also multiplied in painting: the oldest portrait is attributed to Giotto and his workshop, although the most iconic one was painted more than a century later by Sandro Botticelli. And in Rome? In the early 16th century a “divine” painter made his appearance in the city, called by Pope Julius II to fresco his apartments. The cycle of paintings that decorate the Room of the Segnatura decreed his triumph and made him the most sought after artist, competing only with Michelangelo. It is precisely in this room that Raphael paints two fresco portraits of Dante. The profile of the poet, with the characteristic aquiline nose and head crowned with laurel, appears in the lower part of the Disputation of the Most Holy Sacrament, in the company of theologians, doctors of the Church and popes. And we see him a second time among the epic poets depicted in the scene illustrating the Parnassus, with a draped robe and a volume in his hand, half hidden by Homer’s arm. Few refined brush strokes that give us back the austere grandeur of the poet par excellence.

#5 Casino Massimo Lancellotti

Hell, purgatory and paradise in just one room: when in the early 19th century Marquis Carlo Massimo buys the elegant 17th-century casino not far from the basilica of San Giovanni in Laterano, he entrusts the decoration of three rooms to a group of artists intolerant of academic classicism, who had moved to Rome bringing with them a certain German Romanticism and a touch of “biblical” extravagance in lifestyle and hair. For him, the so-called Nazarene painters translate into images Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, Tasso’s Jerusalem Delivered and the Divine Comedy. In Dante’s Room, Philip Veit paints the Paradiso on the ceiling with clear brush strokes and bright colors. However, the most eye-catching frescoes are those painted by Joseph Anton Koch, according to chronicles a passionate reader of Dante’s poem: the scenes of the Purgatorio and, above all, the large wall dedicated to the Inferno, dominated by the gigantic figure of Minos. All around, under the gaze of Dante and Virgil on the back of the monstrous Geryon, there are more or less famous demons and damned, in a tangle of naked bodies, partly retouched and censored by Christina of Saxony, who inherited the casino on the death of her brother-in-law. And who, for the sake of decency, erased Paolo from the fresco, leaving Francesca eternally alone in the hellish storm and wearing a lot of clothes on her.

#6 Pincio Promenade

Logic says the monument to the father of the Italian language should be in the Roman square named after him, that is, Piazza Dante, born in the 1920s in the Esquilino district: indeed, it was planned but never made. The same fate befell the Danteum, a large architectural memorial designed in 1938 to be built along Via dei Fori Imperiali, close to the Basilica of Maxentius. To pay an open-air homage to Dante, all that remains is the Pincio Promenade, the first public park to open in the city. Here, among centuries-old trees and fountains, there are over 200 illustrious men of our past observing us, making up one of the largest collections of commemorative busts in Europe. The idea was born in the years of the Roman Republic, with the intention of forming a national identity and conscience: among the first 50 busts created, Dante could not be missing. It was sculpted in 1849-1850 and then placed between Viale dell’Orologio and Viale degli Ippocastani, in good company with Giotto, Cola di Rienzo and other medieval famous names. This may seem like a small thing but read what Cesare Pascarella – with Belli and Trilussa one of the literary glories of the city – wrote: “Because those busts, before being busts, / Have once been all real men. / And what great men they were! Well over the average. / Envied and admired by the whole world!”.

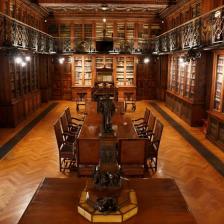

#7 Palazzo Besso, Library

A historic Roman residence overlooking the Sacred Area of Largo di Torre Argentina, of which it forms an elegant architectural backdrop. Enlarged and enriched by its numerous owners over the centuries, then partially demolished in the late 19th century when Corso Vittorio Emanuele II was opened, the building was finally purchased in 1905 by Marco Besso. Here he lived with his family, transforming the building a few years later into the seat of the foundations named after him and his wife Ernesta. A financier, refined bibliophile and writer, Marco Besso was also a passionate scholar of Dante: the magnificent library that constitutes the heart of the house boasts one of the most important and richest collections of Dante’s editions. In an environment made warm and evocative by the wooden furnishings made in 1907, we can find rare 15th- and 16th-century editions and many modern Italian and foreign printed books of the Comedy, as well as critical works, bibliographic repertoires and magazines. If you think it is not enough, just look around you: the image of Dante is everywhere, in the bronze and alabaster reproduction of the monument dedicated to him in Trento, in the gold effigies on the backs of the imposing leather armchairs, in the marble bust of the poet and finally in the copies of the oil cruet and the votive lamp from his tomb in Ravenna.

Engelsburg

Condividi

Condividi

Palazzo Orsini Taverna

Condividi

Condividi

Vatikanische Basilika St. Peter

Condividi

Condividi

Vatikanische Museen und Sixtinische Kapelle

Condividi

Condividi

Casino Massimo Lancellotti (inside Villa Giustiniani Massimo)

Condividi

Condividi

Die Terrasse und Promenade des Pincio

Condividi

Condividi

Besso-Palast

Condividi

Condividi